Practice

Tame the Mind: Insights from the 10 Ox-Herding Pictures

Posted: October 7, 2024

Updated: November 13, 2024

The story of “Taming the Ox,” also known as the Ten Ox-Herding Pictures, is a metaphor in Zen Buddhism that represents the stages of spiritual development and the path to enlightenment. Each of the ten stages is illustrated by a picture of a boy, the practitioner or oxherd, and an ox, the mind. The ox represents one’s true nature or the mind, which is wild and untamed at first but can be brought under control through practice and discipline. Unlike typical transformation stories that focus on the before and after, the ten ox-herding pictures illustrate the entire process, guiding others on the path. Using the stages we can apply these principles to harness the primitive nature of the mind and overcome habitual patterns of thought.

Eastern spiritual traditions and Western psychology share a common goal: transforming consciousness, even though they use different methods to achieve it. Both processes challenge the ego’s dominance, while psychology, Jungian more specifically, seeks to integrate the unconscious into a more complete self, Zen realization aims to dissolve the ego’s illusion and awaken to a state of non-duality, where the self and the universe are seen as one. So, psychology leads to a more whole and balanced self, whereas Zen realization leads to the transcendence of the self altogether. Integrating both schools of thought, we can see enlightenment doesn’t mean getting rid of the self. Instead, it’s about letting go of your ego so you can make space for the self to connect to the unified consciousness.

This exploration integrates the Ten Ox-Herding Pictures with Jungian psychology to understand the process of self-realization through individuation and interconnectedness.

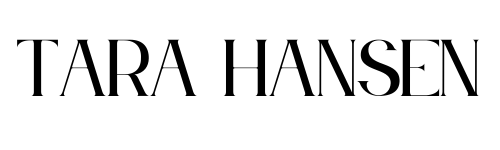

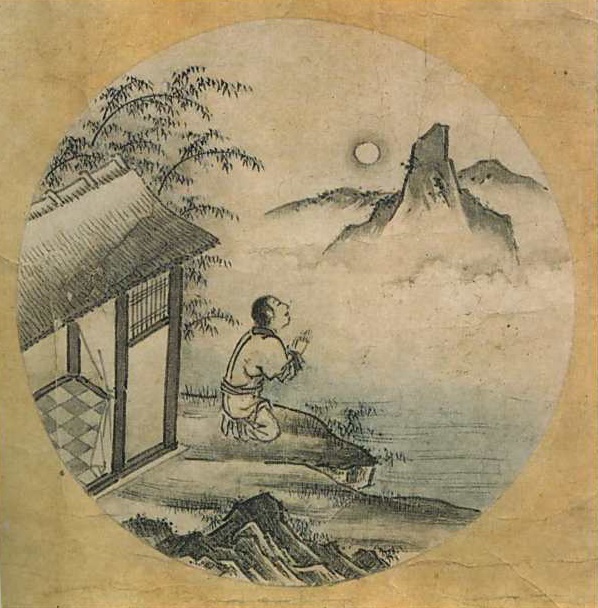

Searching for the Ox

This stage represents the initial search for truth or self-awareness. The practitioner realizes that there is something missing or that the mind is restless, and they begin their spiritual journey to find peace.

From a Jungian perspective, the ox could represent the true Self, or the divine within. Searching for the ox is the inner drive that pushes the Self to understand itself. In the beginning of psychological development, God is concealed in the most clever way, inside oneself. While the oxherd is the ox he is searching for, the feeling of separation shown in Picture One is essential for him to later consciously reconnect and build a relationship with his untamed, unconscious, Self.

Seeing the Tracks

The practitioner sees signs or clues (the tracks of the ox) that point to the presence of the ox. This represents glimpses of one’s true nature or the understanding that the mind can be tamed.

“Seeing” is the same as reading or hearing the story of the Ten Ox-Herding Pictures but not yet having lived each stage of the journey, an indirect experience with your divine nature. This realization often happens when the ego recognizes its limitations and becomes weary of its usual perspectives. As the ego runs out of energy to process its experiences, it starts to open up and listen more attentively. In response, the Self provides a sign or guidance.

Seeing the Ox

The ox (the mind) is spotted. It’s wild and hard to control, but the practitioner recognizes it. This represents a deeper awareness of one’s mind, both its chaos and its potential.

In Picture Three, the oxherd briefly sees the ox, experiencing something profound and beyond words. The ox’s face is missing because it cannot be captured by concepts or symbols. This moment pierces the limited view of the ego and introduces the untamed mind, challenging the oxherd’s sense of Self. This represents a deep encounter with the shadow, serving as the first entry point into the unconscious that the oxherd must navigate. As a result, he opens up to a direct, non-conceptual connection with a reality that once felt unreachable. This stage represents the attainment of Kensho, a direct insight into the true nature of the Self.

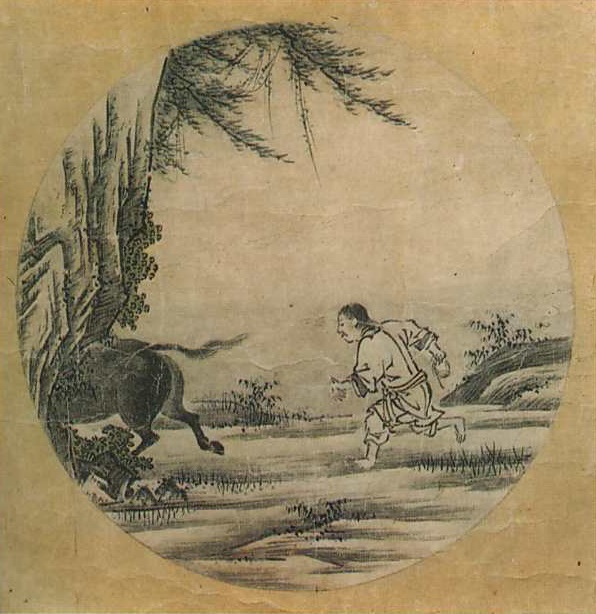

Catching the Ox

The ox is caught, but it still resists. This is the beginning of taming the mind, through discipline and meditation, although it requires much effort.

In the “Found” stage of Zen practice, a student has experienced Kensho, a glimpse of Buddha-nature, but easily falls back into dualistic, good and bad, thinking. This is a gradual process that usually requires a lot of time and patience to achieve. To tame the ox, the mind, the oxherd must hold it tightly but realizes that it is his own attitude that needs to change for the ox to bond with him. Efforts to domesticate the ox aim to make it more predictable and controllable, but the unconscious resists being consumed by the ego. The ego struggles between wanting to connect with this untamed aspect and trying to dominate it. Ultimately, the ox reflects back the attitude of the oxherd, just as the unconscious mirrors our approach to it.

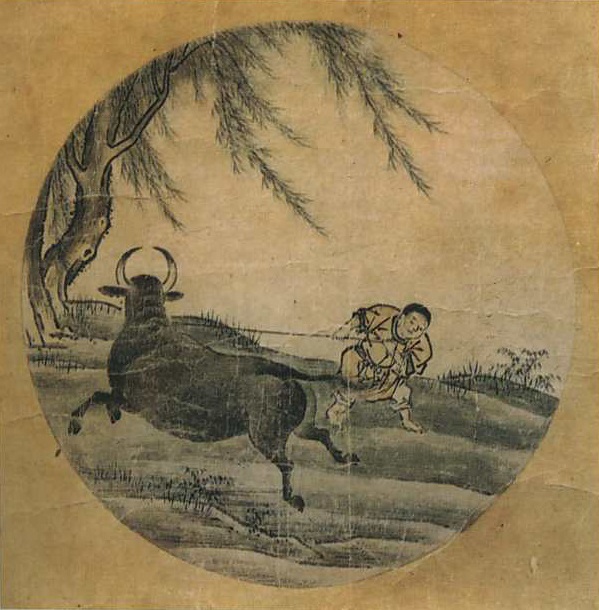

Taming the Ox

The ox becomes more manageable. The practitioner develops greater control over their mind, achieving some degree of inner peace and mindfulness.

In Picture Five, the ego begins to unify with the Self, marked by consistent practice. The ox willingly chooses to accompany the oxherd after he lays down the whip, highlighting that control is an illusion. The oxherd’s efforts must reach a point of exhaustion, similar to how Kensho occurs when mental striving ends. The loosened rope between the oxherd and the ox symbolizes a gentle release of the ego’s tight grip on the unconscious mind, allowing the ox to exist freely without the ego’s possessive desires.

Riding the Ox Home

The ox is now calm, and the practitioner rides it back home. This represents the harmonious relationship between the mind and the self, where the practitioner is more centered and in control of their thoughts.

In Picture Six, the oxherd has completely let go of the rope, realizing that trying to drive the self forward and understand everything is an illusion. True awakening occurs when everything emerges and illuminates the self, rather than the self creating its identity. The conscious self learns to release the belief that it is in control and instead surrenders to being guided. Both the oxherd and the ox resist domestication, embodying a raw, unfiltered way of knowing and communicating. However, because the oxherd does not meet the ox’s gaze, their relationship is not yet fully realized.

Ox Forgotten, Self Remains

The ox has been tamed to the point where it is no longer a concern, and the focus shifts to the self. This stage represents the deepening of spiritual practice, where distractions fall away, and one is more attuned to their true nature.

The self and the ox become one, and Satori represents the unity between self and Dharma, where the individual and the ox form a single entity. Instead of trying to capture or control the ox, the oxherd now humbly respects the wild nature of the mind. He takes a backward step, moving away from the external world to turn inward, experiencing a union infused with the ox’s wild spirit. This fulfillment allows him to give the ox space, freeing it from being used merely as a means to achieve awakening.

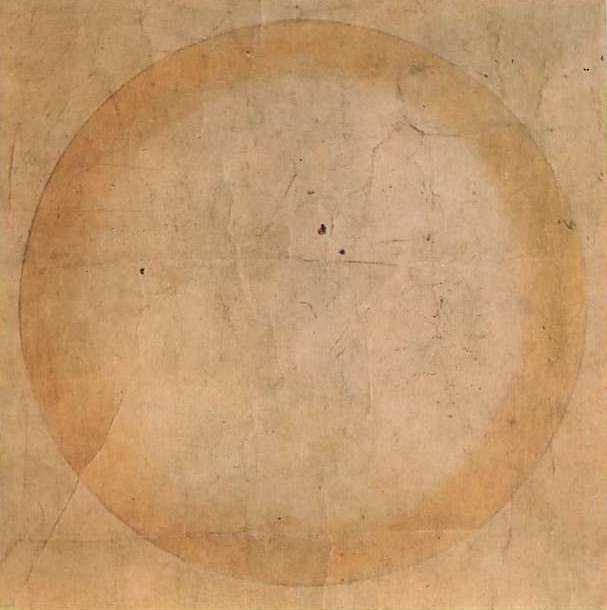

Both Ox and Self Forgotten

Even the concept of self dissolves. This stage signifies the attainment of true enlightenment, where there is no distinction between self and the world. Everything is unified.

In Picture Eight, both the ox and the oxherd are absent, leaving an empty circle that symbolizes Sunyata, or Buddhist emptiness, often referred to as the Great Death. This concept represents a transformation into both everything and nothing, as it penetrates the depths of the mind and becomes completely one with it. Here, the ego encounters the Self that it cannot control or assimilate. The term “moku,” which signifies silence, emphasizes entering a state of absolute stillness that remains undisturbed by speech and enriches it with deeper meaning. This process of silencing and emptying involves shedding human identity and its expressions. In the emptiness of the Enso, the division between man, animal, nature, and the world is erased, allowing for a fresh stream of consciousness to emerge.

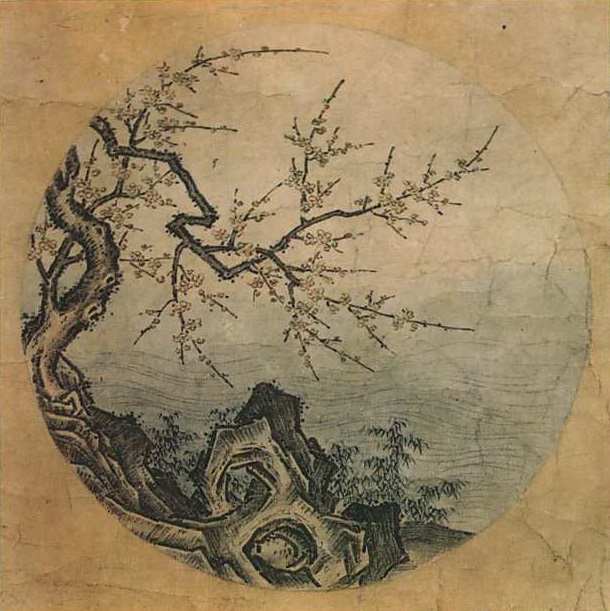

Returning to the Source

Having realized enlightenment, the practitioner returns to the simplicity of life, recognizing that the essence of existence is beyond concepts or dualities. It’s a return to the natural state.

After the Great Death comes a resurrection into Great Life, as shown in Picture Nine, where the world is seen anew and the oxherd’s projections are removed. In the heart-mind, there is an emptiness that is inseparable from the universe. It becomes clear that the ox cannot be attained because the oxherd is already what he seeks. Just as alienation is essential for individuation, the separation from the ox was necessary for the oxherd to turn back and truly see it. The ox serves merely as a symbol or tool for teaching self-realization, which can be discarded once it has served its purpose. By relating to the ox as a subject, the oxherd deepens his connection with the ox within himself.

Entering the Marketplace with Open Hands

The final stage represents re-engagement with the world. After attaining enlightenment, the practitioner returns to society with a heart open to help others, embodying wisdom and compassion in daily life.

Picture Ten is often seen as depicting the oxherd as a Bodhisattva, a compassionate figure who returns to help others recognize their Buddha-nature after achieving enlightenment. From a Jungian perspective, this image reflects the individuated ego’s sacrificial mindset. Having been emptied in service to the Self, the oxherd continues to release and let go by emptying his sack. He establishes a conscious relationship with the Self, remaining neither alienated from nor overly identified with it. This journey toward individual Selfhood reveals the interconnectedness of relationships, showing that being “one” inherently involves an interconnectedness with others.

The story of taming the ox is a beautiful illustration of the inner spiritual journey, emphasizing that enlightenment is not an escape from the world but a transformation of one’s relationship with it through an internal shift in awareness. We find similar narratives in other religions, such as the Good Shepherd and his Sheep in Christianity, which symbolizes the process of salvation and spiritual growth through faith in the divine. The culmination of these journey’s reflects a connection to the eternal and liberation from attachment through a deeper truth.

Over the years I have found loops in the path that have brought me back to earlier stages in the path. The challenge is to reenter the world with a fresh perspective, avoiding a relapse into old emotional patterns and habits. A reminder of our birth, sustenance, and death cycles that encompass the spiritual journey and a human life. To either lose our way and find ourselves back at the beginning, or in new terrain that is unfamiliar. We are in a constant cycle of creating, sustaining, and ending within each breath. Presence in the journey, and patience with the self, ground us in the wonder of being exactly where we are.

“Be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and try to love the questions themselves, like locked rooms and like books that are now written in a very foreign tongue. Do not now seek the answers, which cannot be given you because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps you will then gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into the answer.” / Rainer Maria Rilke

Granovetter, S. (2024). Wild Otherness Within: A Jungian and Zen Approach to the Untamed Self in the Ten Oxherding Pictures. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 42(2), 133–152. https://doi.org/10.24972/ijts.2023.42.2.133

Stein, M. (2019). Psychological Individuation and Spiritual Enlightenment: Some Comparisons and Points of Contact. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 64(1), 6–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5922.12462

© 2024 Tara Hansen, LLC